What is the pancreas?

The pancreas is a major organ in the body, usually around 6 inches long, which plays an important role in digestion and hormone release.

Where is the pancreas?

The pancreas is located behind and below the stomach at the level of the L1 vertebra.

The pancreas can be divided into five distinct parts:

- Head – the C shaped duodenum curves around the pancreatic head. The aorta and inferior vena cava (IVC) pass behind the pancreatic head.

- Uncinate process – the superior mesenteric artery (SMA) runs in front of the uncinate process.

- Neck – the SMA runs behind the neck of the pancreas, in addition to the splenic and superior mesenteric veins, which merge to form the hepatic portal vein.

- Body

- Tail – lies closely to the spleen, and is the only section of the pancreas which lies within the peritoneum i.e., within the abdomen.

What does the pancreas do?

The pancreas has both an endocrine and exocrine function i.e., it secretes digestive enzymes (exocrine) and makes and releases hormones (endocrine).

Pancreatic endocrine function

The pancreas contains Islets of Langerhans, which are clusters of different hormone-producing cells.

| Cell Type | Hormone Release | Action |

| Alpha | Glucagon | Increases blood glucose level. Stimulates Alpha cells. Activates Beta and Delta cells. |

| Beta | Amylin | Prevents sudden spikes of blood glucose by regulating gastric emptying. |

| Beta | Insulin | Reduces blood glucose level. Stimulates Beta cells. Inhibits Alpha cells. |

| Delta | Somatostatin | Inhibits the release of pancreatic hormones, targeting Alpha and Beta cells. |

| Gamma | Pancreatic polypeptide | Controls the release of pancreatic hormones. |

| Epsilon | Grehlin | Increases appetite. |

Pancreatic exocrine function

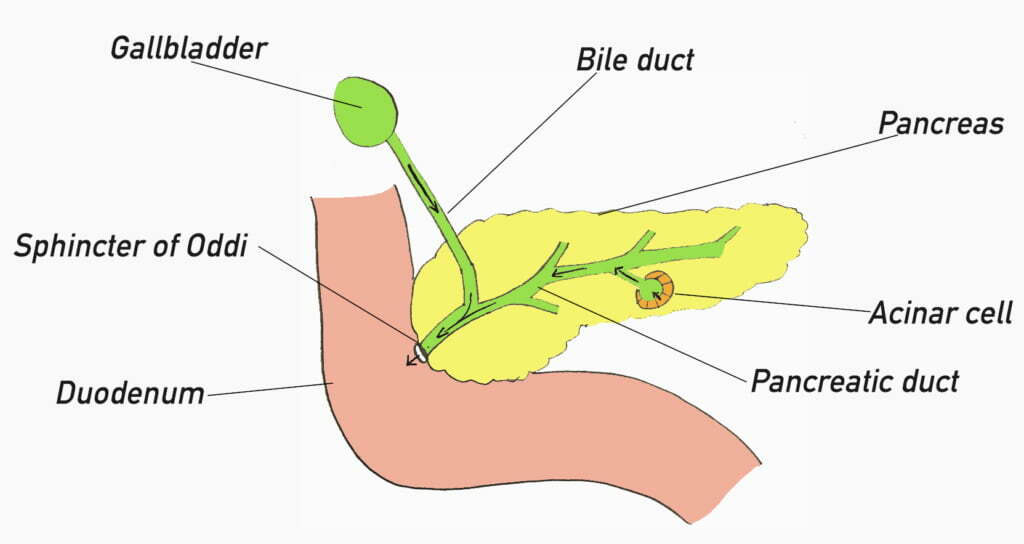

The pancreas contains acinar cells which synthesise, store, and secrete:

- Digestive enzymes

- Water

- Bicarbonate – this neutralises stomach acid upon entering the duodenum.

After being secreted from the acinar cells, the products enter the main pancreatic duct which merges with the bile duct at the head of the pancreas, forming the Ampulla of Vater. The release of these contents into the duodenum is controlled by the sphincter of Oddi, a muscular valve.

What is pancreatic cancer?

There are numerous types of pancreatic cancer, identified by the type of cell the malignancy starts in. Consequently, an individual can have exocrine pancreatic cancer or endocrine pancreatic cancer, reflecting the two functions of the cells of the pancreas. Further, pancreatic cancer may be classified according to where in the pancreas it is located; most pancreatic cancers start in the head of pancreas.

Exocrine pancreatic cancer

The most common form of exocrine pancreatic cancer is ductal adenocarcinoma. However, there are also less common exocrine pancreatic cancers including:

- Cystic

- Acinar cell carcinoma

- Ampullary carcinoma i.e., developing in the ampulla of Vater.

- Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm (IPMN) – mucus producing carcinoma in the pancreatic duct.

Endocrine pancreatic cancer

These are most commonly known as pancreatic neuroendocrine tumours (NETs) or Islet cell tumours. Depending on which cell the tumour derives from will decide which signs and symptoms an individual may have. Pancreatic NETs can therefore be categorised as follows:

- Insulinoma – leads to increased levels of insulin being produced and therefore very low levels of blood glucose. These usually develop in the head of the pancreas and are benign.

- Gastrinoma – leads to increased levels of the hormone gastrin which increases the amount of stomach acid produced. Symptoms therefore include: stomach ulcers and diarrhoea (Zollinger-Ellison syndrome), gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD), and pain in the abdomen. These usually form in the head of the pancreas and small intestine and are malignant.

- Glucagonoma – leads to increased levels of glucagon and therefore high levels of blood glucose. Symptoms are reflective of the high glucose levels and include thirst, polyuria, fatigue, weakness, headaches, and dry skin. These usually develop in the tail of the pancreas and are malignant.

What are the risk factors for pancreatic cancer?

- A positive family history in a first-degree relative

- Increased age

- Smoking

- Obesity

- Chronic pancreatitis

- Diabetes

- Gallstones

- Metabolic syndrome

- High levels of alcohol consumption

- Genetic disorders:

- Peutz-Jehgers syndrome

- Familial atypical multiple mole melanoma syndrome (FAMMM)

- Lynch syndrome/hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC)

What are the symptoms of pancreatic cancer?

Pancreatic cancer is often very late in presentation. Due to the location of the pancreas being deep within the body, signs and symptoms usually only develop once the tumour has spread and/or grown to a significant size.

The key signs and symptoms that clinicians should be vigilant for include:

- Dull stomach pain, that may travel to the back, and is worse on lying down or after eating.

- Jaundice

- Unintentional weight loss

- Loss of appetite

- New onset diabetes

- Itching

- Nausea

- Steatorrhea (fatty stools – pale, foul smelling, and difficult to flush)

- Fever and rigors

- Indigestion

- Blood clots

How is pancreatic cancer diagnosed?

A person with suspected pancreatic cancer will undergo a series of investigations:

- Blood tests

- Scans

- CT scan

- Fluorodeoxyglucose PET scan

- Endoscopic ultrasound scan (EUS)

- Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP)

- Biopsy and carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) assay

- Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP)

What treatment can be given for pancreatic cancer?

Treatment of pancreatic cancer is often targeted at relieving symptoms through surgery, although surgical resection may be attempted with intent to cure.

Surgical resection is offered when the cancer has been diagnosed early and has shown no signs of spread. An individual may have borderline resectable pancreatic cancer, where the tumour is growing close to the major blood vessels; further detailed investigations will need to be performed to assess how viable surgery will be.

Symptoms can be managed palliatively through:

- Bypass surgery – disconnecting the stomach and/or bile duct from the duodenum, and connecting it to a lower part of the small intestine, thus bypassing any small intestine affected by a pancreatic tumour.

- Duodenal stenting – to keep the duodenum open, allowing food to pass from the stomach into the small intestine.

- Biliary stenting – to aid flow of bile through the bile duct.

- Whipple’s operation – removing cancer in the head of pancreas.

- Distal pancreatectomy – removal of the tail, and perhaps a small portion of the body, of the pancreas.

- Total pancreatectomy – removal of the entire pancreas.

- Vein resection – if the cancer has grown into the surrounding major blood vessels, it may be possible to resect the invaded section of the vein.

Can pancreatic cancer be cured?

Pancreatic cancer is often very late in presentation, as symptoms only develop once the tumour has spread and/or grown to a significant size. Pancreatic cancer is also far less responsive to traditional cancer treatments such as chemotherapy and radiotherapy. And only 10% of individuals will be suitable to undergo resection of the pancreatic cancer, which gives the best chance of survival. Overall, the prognosis and survival rates for pancreatic cancer are poor, however vary according to their stage.

Localised pancreatic cancer i.e., that has not spread outside the pancreas, has a 40% five-year survival rate.

Regional pancreatic cancer i.e., that has spread to the local lymph nodes, has a 15% five-year survival rate.

Distant pancreatic cancer i.e., that has spread to another part of the body, has a 5% five-year survival rate.